The IoT in Cyberspace Operations and Cyber-Electromagnetic Activities

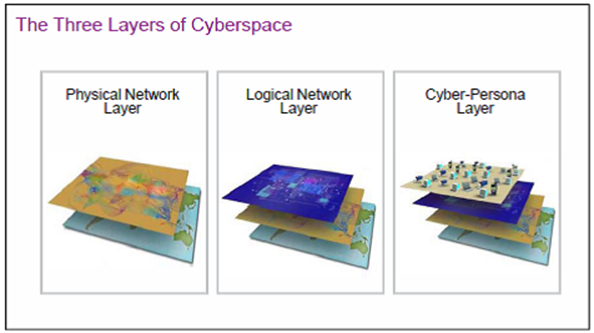

For both critical infrastructure and non-critical infrastructure owners, it is important that they understand that regardless of whether or not their IoT devices are connected to a closed TCP/IP network or to the Internet, they are a target on a battlefield within the fifth domain of warfare, which is cyberspace. According to Joint Publication (JP) 3-12 (R) Cyberspace Operations, there are three layers of cyberspace: the physical network layer, the logical network layer, and the cyber-persona layer. The definitions are lengthy and can be summarized as follows:

Image Credit: CJCS JP 3-12 Cyberspace Operations (see here)

A. Physical Network Layer

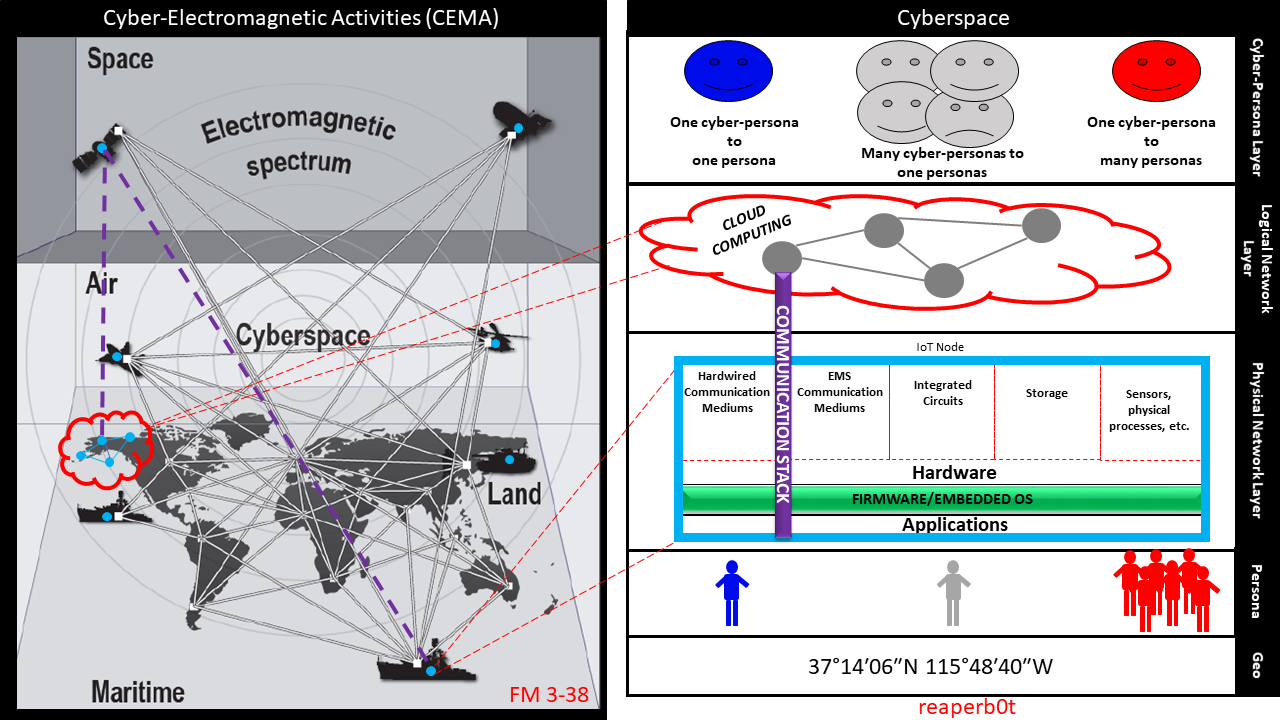

JP 3-12 defines the physical network as the geographic component (land, air, sea, or space) where the network resides and physical network components comprised of the hardware, systems software, and infrastructure that supports the network [3]. This layers used logical constructs as the primary method of security [3]. We would like to add that a network does not always imply a TCP/IP network. A network can be a simple CAN bus network in a vehicle or Modbus network between a master and slave PLC. In addition, we also present the fact that a node within cyberspace can be disparate. Specifically, there are IoT devices that are not connected to any network or they are only connected to a network on certain occasions, but they can still have both offensive and defensive cyber effects applied, especially through interfaces which can be accessed through the electromagnetic spectrum (e.g. 802.11x enabled devices). Due to this disparity, the term physical network layer is misleading and should be changed to just the physical cyberspace layer. The electromagnetic spectrum (EMS) exists at the physical network layer, through which electronic warfare and subsequently cyber electromagnetic activities (CEMA) can be applied. CEMA is discussed later in this section.

Image Credit: Army FM 3-12 Cyberspace and Electronic Warfare Operations (see here).

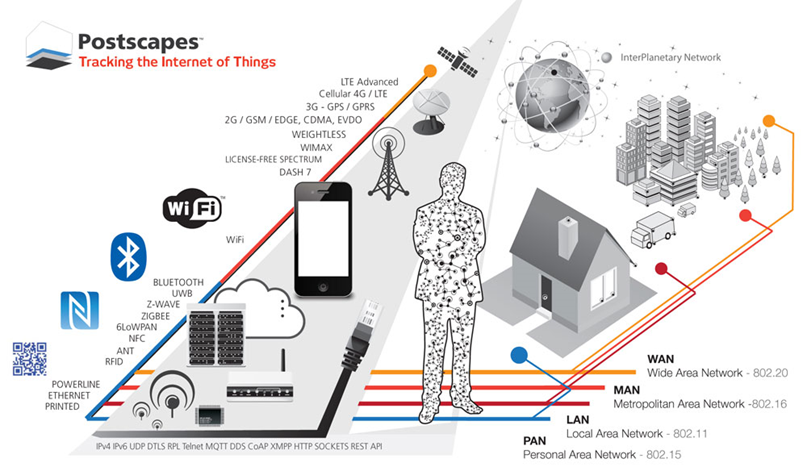

Postscapes' "connectivity diagram" incapsulates some of the wireless protocols in use by the IoT.

Image Credit: Postscapes.com (see here)

List of Common IoT Wireless Protocols (Compiled from list here)

- RFID

- ANT/ANT+

- NFC

- 6LoWPAN

- Thread (Google)

- ZIGBEE

- Z-WAVE

- UWB

- Bluetooth / BLE

- WiFi

- DASH 7

- License-Free Spectrum

- WIMAX

- WiFi-ah (HaLow)

- WEIGHTLESS-N/-P/-W/

- 2G/GSM/EDGE, CDMA, EVDO

- 3G-GPS/GPRS

- Cellular 4G / LTE / LTE-M1/ LTE Advanced

- Narrowband IoT (NB-IoT)

- 5G

- SigFox

- LoRaWAN

- Ingenu

- DigiMesh

- MiWi

- EnOcean

- WirelessHART

B. Logical Network Layer

The next higher layer described by JP 3-12, the logical network layer consists of those elements of the network that are related to one another in a way that is abstracted from the physical network, i.e., the form or relationships are not tied to an individual, specific path, or node [3]. An example is given using a website that is hosted on servers in multiple locations where all content can be accessed through a single uniform resource locator (URL) [3]. We would also like to extend this layer to include items such as cloud computing services and VPNs, that allow an otherwise geographically disparate node to logically replicate a physical connection.

C. Cyber-Persona Layer

According to JP 3-12, the cyber-persona layer consists of the people actually on the network [3]. A cyber-persona is the projection of a persona into cyberspace. Additionally, JP 3-12 states that cyber-personas may relate fairly directly to an actual person or entity, incorporating some biographical or corporate data, e-mail and IP address(es), Web pages, phone number, etc [3]. It is possible for a person to have a one-to-one persona to cyber-persona or a one-to-many persona to cyber-personas. It is also possible for a group of people to have many-to-one persona to cyber-persona, which makes attribution to a specific individual difficult [3]. However, some or all of the details in a cyber-persona can be inaccurate, outdated, or outright false.

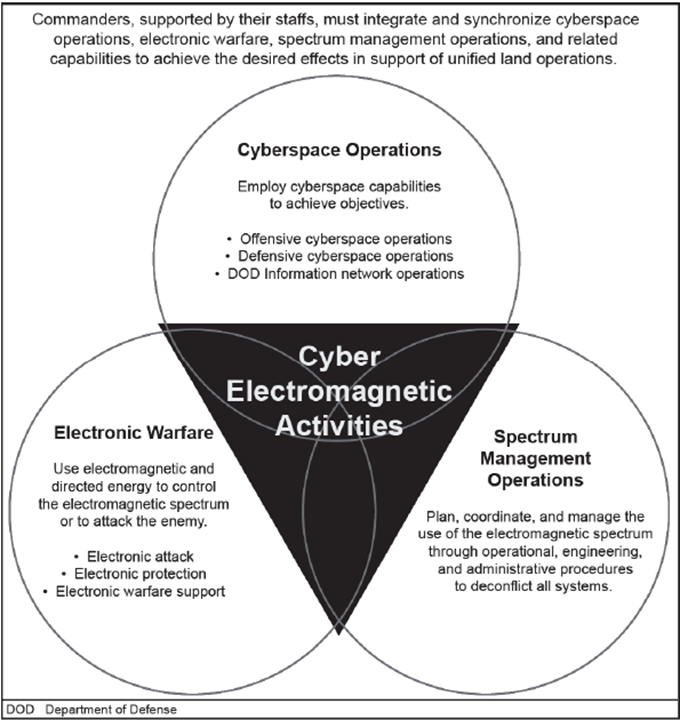

Cyber-Electromagnetic Activities (CEMA)

Image Credit: US Army FM 3-38 (see here)

Army Field Manual (FM) 3-38 Cyber Electromagnetic Activities, (which has been superseded by FM 3-12 as of APRIL 2017), defines CEMA as the consummation of cyberspace operations (CO), electronic warfare (EW), and spectrum management operations (SMO) [4]. FM 3-38 further designates that CEMA is leveraged to seize, retain, and exploit an advantage over adversaries and enemies in both cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum, while simultaneously denying and degrading adversary and enemy use of the same and protecting the mission command system [4].

EW, can be used to affect IoT devices, specifically through electronic attack (EA) and electronic warfare support (ES). FM 3-38 defines EA as the use of electromagnetic energy, directed energy, or antiradiation weapons to attack personnel, facilities, or equipment with the intent of degrading, neutralizing, or destroying enemy combat capability and is considered a form of fires [4]. EA tasks include countermeasures, electromagnetic deception, electromagnetic intrusion, electromagnetic jamming, electromagnetic pulse, and electronic probing [4]. FM 3-38 defines ES as actions to search for, intercept, identify, and locate or localize sources of intentional and unintentional radiated electromagnetic energy for the purpose of immediate threat recognition, targeting, planning, and conduct of future operations [4]. ES tasks include electronic reconnaissance, electronic intelligence, and electronics security [4].

Both EA and ES apply directly to IoT devices, regardless of whether or not the IoT device has an interface capable of communicating through the electromagnetic spectrum. This is evident with the publishing of information regarding TEMPEST activities, which refers to the spying on information systems through leaking emanations, including unintentional radio or electrical signals, sounds, and vibrations [5]. Furthermore, attacks against 802.11x using attacks directed at the 2.4GHz and 5GHz frequency (e.g. jammers) as well as the protocol itself (e.g. deauthentication attacks) provide insight into what both EA and ES would look like from the perspective of IoT devices.

When abstracting cyberspace out of CEMA, imagine that it is looks something like this:

Image Credit: reaperb0t (Daniel West) and US Army FM 3-38

Image Credit: reaperb0t (Daniel West) and US Army FM 3-38

Image Credit: Army FM 3-12 Cyberspace and Electronic Warfare Operations (see here)